There’s been some discussion on the reasons why we might romanticise retro games, game preservation and particularly the idea of “just buy a game and play” recently.

Specifically, it was prompted by this tweet from Matt Gardner, editor of GameTripper and games writer at Forbes:

It’s understandable that some people might be getting fatigued with this argument — particularly if they’re a fan of what gaming is doing today.

And, to be sure, there are a lot of interesting and exciting things going on in gaming today — some of which wouldn’t be possible without the introduction of technology such as the Internet.

But there’s some validity to this argument that means it’s more than just looking back on the past with rose-tinted spectacles. And, as with all things retro, it all comes back to preservation.

A matter of preservation

Right now, as a result of preservation efforts, it is possible to obtain a pretty much complete archive of every game available for the first six generations of games consoles. While certain methods of distribution of these games is a matter of continuing, ongoing moral debate, the fact that you can download complete ROM sets for various systems from the Internet Archive, of all places, shows that a significant number of people are taking the preservation of gaming seriously.

On top of that, organisations such as the Game Preservation Society are making great strides in preserving material from platforms that had no physical presence, such as the i-Mode mobile phone service that was popular in Japan.

The point of preservation is to maintain a complete, accurate library of everything that was released for a particular platform, so that we can look back on it, learn from it and simply enjoy it. It’s the same reason that books from hundreds of years ago are endlessly reprinted, classical music is truly timeless, and art by the great masters is treated with such reverence: future generations deserve the opportunity to experience the creative work of the past.

Here’s the problem, then: from about halfway through the seventh generation of video games consoles, when patches and DLC became an ever-present part of the gaming landscape, preservation became infinitely more difficult. While, yes, you can still acquire disc-based copies of many — though not all — games, in many cases, the versions of these games on the discs they shipped on was not their best. And in other cases, the games expanded so much over time as to be unrecognisable from their original retail release.

Square Enix’s Final Fantasy XV is an example of both of these issues. Play the version that was originally released on disc, and you’ll find a buggy mess that just about functions as a video game. Immediately after launch, it was patched into a playable state. But then over the following months, it was patched further and updated with DLC that completely revamped its gameplay, expanded its story and made it a completely different package to what it was when it first arrived on the scene.

How do you preserve that, then? Do you preserve the original on-disc version? You could, but then Final Fantasy XV’s legacy is a completely broken mess that is barely playable. Do you preserve the version as it exists today after all the patches and DLC? That would make sense — but it doesn’t provide an accurate picture of how most people experienced it on launch. Do you preserve the game as it existed with its day-one patch in place? Perhaps, but how do you propose you do this, given that today’s consoles don’t have any sort of “version control” in place?

Arguably the optimal answer is to preserve the game as it was originally released and then all the patches that became available over time, allowing future gaming historians to pick the exact version of the game they want to experience.

But in the case of some games there are so many patches and updates that this is completely impractical, even without taking into account the fact that we haven’t yet figured out a reliable means of archiving patches for when various generations of PSN or Xbox Live servers inevitably go down. Take something like Minecraft or Terraria — or the myriad games that are perpetually in Early Access. How do you preserve those experiences when they’ve had so many updates over the years, some of which radically changed the experience?

This is the crux of why a lot of people think that things were better in the past. Right now, today, we can respect and enjoy every part of the first six generations of gaming, with no question over whether or not we’re experiencing these games as people did back when they were first released.

When it comes to the second half of the PS3/360 generation, the entirety of the PS4/Xbox One generation and beyond, though, the question of preservation becomes much more difficult. And no-one seems to have found any really good answers as yet.

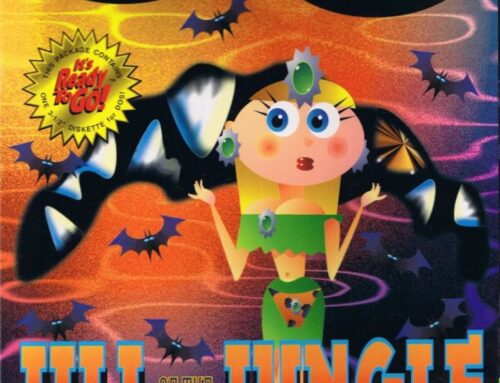

That’s why “just buy a game and play” remains a valid and helpful argument. Buy a copy of a SNES game today — be it Super Mario World or some licensed game that everyone forgot immediately after it was released — and it plays like it did when it was first released. But buy a disc copy of a PS4 game in 20 years time and there’s no guarantee it will even work at all. And that kind of sucks.