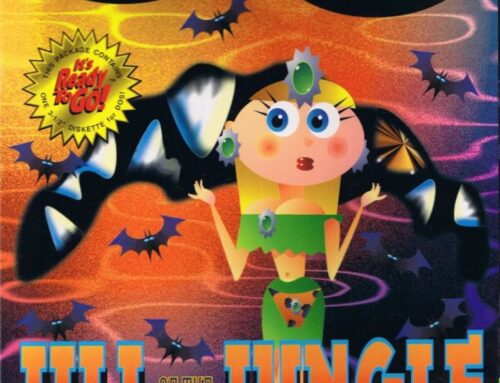

These days, we’re pretty familiar with the idea of free software of various forms: freeware, open-source projects, free mobile apps (although nine times out of ten these days, those aren’t actually free) and all manner of other things. Back in the 8- and 16-bit home computer era, public domain software was the main means through which free software was distributed — and it’s from the world of public domain that today’s strictly unofficial, unlicensed version of Q*Bert hails.

The game itself is fairly self-explanatory, so I’ll leave the video to speak for itself; however, it is worth talking a little more about the public domain phenomenon, because it was very much part of home computing culture during this period — and, moreover, its history has not been chronicled all that well!

The public domain (or “PD”) scene in this era of home computing is fascinating, because it’s full of an absolute wealth of excellent software — both for entertainment and productivity. Demoscene groups were at their peak, hobbyist (and professional!) game developers were happily putting their work out for free, and if your computer didn’t do a thing very well you could count on some resourceful utility developer to sort that problem out for you before long.

There was just one problem, the solution to which we take for granted today: distribution. While online connectivity over the telephone lines via dial-up modem was absolutely a thing, widespread Internet access did not take hold until the mid-’90s, which is when most people had moved on to MS-DOS and Windows 95 PCs.

Back in the age of the Atari ST, the computer which plays host to this version of Q*Bert, most people’s online access was limited to bulletin board systems, which, being typically run by individuals or small groups at best, tended to have a limited capacity for software they could make available for download. On top of this, computer users typically didn’t have access to hard disks, so anything you were able to download needed to be able to fit on a floppy disk.

In other words, while there was a lot of free software out there back in the days of the Atari ST, there was no central repository — no Internet, so far as the average user was concerned — where all this software could be dumped so that anyone and everyone could download it, and so alternative solutions were required.

Enter the phenomenon of public domain libraries, which were organisations that collected together all this free software, organised it into convenient floppy disk packages, then sold these disks on to end users.

The licensing agreements for public domain software usually precluded these libraries from profiting directly from the sale of an individual piece of software, but it was commonly understood that providing a service like this incurred expenses: media costs, postage fees and simple time. As such, no-one seemed to mind that public domain libraries charged: after all, from a developer’s perspective, they were helping get their software in front of more people, and from an end user’s perspective, there was no other way they could get their hands on this software in many cases!

Page 6 magazine and its role in popularising public domain software

One of the largest public domain libraries for the Atari ST specifically was part of the operation run by an Atari-centric magazine called Page 6 (later New Atari User) in the United Kingdom. By the end of the magazine’s lifespan, there were well over a thousand disks available from the Page 6 ST Library — and another 400+ for Atari 8-bit computers. All of these disks for both platforms have been archived over at page6.org, an enthusiast-run site chronicling the history of the magazine and the culture surrounding it.

Page 6 was a long-running magazine, surviving from 1982 until 1998, long after all other Atari-based magazines had bitten the dust. Although the magazine did enjoy a successful stint on newsstands in the middle of its lifespan, for much of the time it was available it was a subscription-only publication, dependent on contributions from readers for each bi-monthly issue’s content, and on its related business ventures such as its accessory and software mail-order services for sufficient budget to keep the lights on and the printing presses rolling.

The Page 6 Library was, of course, a big part of that. With disks costing somewhere between £3.95 and £5.95 each, there was enough value in each transaction to help keep the magazine afloat a lot longer than if it had been dependent on advertising revenue. Editor Les Ellingham believed in the value of the Library so much that in the magazine’s latter days, after it had left newsstands, he encouraged readers to make a commitment to purchase at least two public domain disks from the Library each issue. Many readers happily took him up on that offer, knowing that they would be getting some excellent value disks full of software for their favourite computers.

With that many disks in the Page 6 ST Library, I honestly have no idea if the version of Q*Bert seen above was ever available via Page 6; chances are it was, though, since at one point or another pretty much every piece of public domain, freeware, shareware, donationware and any other kind of “-ware” you’d care to mention probably made it through that software library at one point or another.

These days, acquiring new software is certainly a whole lot more convenient. But I won’t lie; there was always a certain magic in picking up a few new public domain disks and diving into their contents, never quite knowing what to expect… and what hidden secrets might be lurking somewhere on each disk!