Piko Interactive have been doing some great work in game preservation of late. Not only have they been porting old games to new platforms (and indeed other old platforms), but they’ve also been highlighting a bunch of games that are often forgotten by what the world considers to be canonical gaming history. Games like Switchblade.

Y’see, despite the fact that the 8- and 16-bit home computer eras played host to some excellent, imaginative and creative games, when talking about gaming history today, most people tend to focus on gaming consoles, whether it’s the Atari 2600, the NES, the Mega Drive or the PlayStation. And so one inventive way to solve this situation is to take one of those classic home computer games and port it to a classic console. Problem solved. Sort of.

Anyway, that’s what has happened with Switchblade several times at this point; it originally released on Atari ST in 1989, and has, more recently, seen ports to both Sega Mega Drive and the Atari Jaguar, the latter of which is the version we’ll be looking at today. (The Mega Drive version can also be enjoyed as part of the Piko Interactive Collection 1 cartridge for the Evercade, too.)

The Jaguar might seem like a strange console to do a new port of an oft-forgotten game too, but it actually makes a lot of sense. While the Jaguar failed hard on its original launch — mostly because it was incapable of living up to most of the lofty promises Atari made prior to launch, and that Atari subsequently completely ballsed up marketing the thing after it launched — in more recent years it has become quite beloved of the homebrew community, who have found a much more appropriate use for the platform.

That use is something that a lot of people thought Atari should do back in the day when they originally announced the Jaguar: produce a “consolised” version of the Atari ST. While the ST lacked the graphical and auditory oomph of its main rival the Amiga, it still played host to a bunch of great games, many of which would have played excellently on the living room TV.

What we’re seeing now with new Jaguar releases like Switchblade and Head Over Heels is what might have been: what if some well-regarded Atari ST games were available on cartridge and could be played on a console hooked up to the television? The answer is: we could all have a thoroughly lovely time, and remind ourselves that there were plenty of interesting things going on in 1989 besides whatever Nintendo gave its Seal of Quality too.

Anyway, Switchblade. In Switchblade, you take on the role of Hiro, last of the order of Blade Knights, in an attempt to rid the world of the dreaded Havok — Hiro’s more of a PhysX sort of guy.

In order to achieve this lofty goal, Hiro will need to track down the legendary Fireblade, which, rather inconveniently, has been shattered into sixteen equally-sized pieces and scattered through a huge underground complex. And said underground complex is, of course, full of tricks, traps and robotic beasties who would like nothing more than to carefully examine the biological processes which occur when spiky objects are forcibly inserted into a fleshy human anus.

The game was developed by Core Design’s co-founder Simon Phipps, though since Phipps was working on it as a passion project in its free time meant that his notorious “masocore” platformer Rick Dangerous actually made it to market first.

Phipps was determined to bring Switchblade to the world, though; it was a means of expressing his love for Japanese popular media such as Akira (which had released the year prior to Switchblade being completed) as well as an attempt to create a game for the Atari ST that felt like classic arcade and console games.

Since the game was developed for Atari ST as its lead platform, Phipps was able to design the game bearing the computer’s known inherent limitations into account. The ST was pretty bad at smooth scrolling, for example, so he made the game a “flick-screen” adventure — but also incorporated a “fog of war” system which gradually revealed rooms on the screen as the player entered previously unexplored areas.

Likewise, the system’s limitations on colour (16 on screen out of a possible 512, or 4096 on the later STE model) lent the game its distinctive aesthetic; Switchblade is primarily presented in shades of grey, with the main splashes of colour being shades of red and crimson. While there’s not much variation in the overall “look” of the game once Hiro enters the underground complex, few could deny that Switchblade has a distinctive aesthetic to it.

Switchblade is also noteworthy for being an open-structure, exploration-centric game rather than unfolding in discrete levels. While this sort of game design is often attributed to Nintendo’s Metroid and Konami’s Castlevania, European game designers on 8- and 16-bit home computers had been experimenting with it since the early ’80s; famous Spectrum game Jet Set Willy, for example, featured a fully explorable open-structure map a full two years before Metroid showed up.

The nice thing about Switchblade is that although the whole thing basically unfolds as one continuous “level”, it still has clear, well-designed routes that mean you never feel like you’re getting off track or required to double back on yourself. The game features a clear visual language that you’ll learn to parse as you play, including determining which blocks are breakable, which “walls” are actually doorways, and which pits are dangerous to fall down.

Phipps rather sensibly designed the game to have a rather sedate pace, too, despite its inspirations from fast-action anime and manga. The unusual combat system involves holding down a button to charge up an attack, with Hiro unleashing a particular martial arts move according to where the charge meter is when you release it. A quick tap will do a weak jab, a moderate charge will result in a high kick, and a full charge will give you a powerful sweeping kick.

While this might sound cumbersome, the enemy behaviour is designed with this in mind — it’s all about timing. Simply touching an enemy in many cases won’t deal damage to Hiro; he’ll only get hurt if they’re doing an attack animation at the time. And in the rare cases where enemies are painful to the touch, they move in regular, set patterns that you’ll need to hop into and dispatch them on their next pass.

There are some collectible weapons along the way, too, many of which are projectiles. Honestly, though, in a lot of cases these are a bit more trouble than they’re worth; the more useful power-ups come in the form of increases to the starting level of the power meter and the speed at which it charges, making it easier to use the more powerful attacks.

Switchblade has quite a “stiff” feel in comparison to Japanese platformers from the period, and this is likely where some people will find themselves having to take a bit of time to adjust to how the game does things. Once you do, however, you’ll find that you can easily calculate whether or not Hiro is capable of making a jump just by looking at the screen and counting tiles.

This is actually remarkably similar to how Core Design’s original Tomb Raider did things in 3D nearly a decade later — though Phipps wasn’t involved directly in that, it shows that this sense of “uniformity” was a key part of European game design for quite some time.

The open-structure style of the game might seem fundamentally incompatible with a platform that doesn’t typically offer game saves, but this is where Phipps’ inspiration from arcade and console games comes in. Switchblade features a robust scoring system, rewarding you with points for defeating enemies, finding hidden items and defeating bosses, so there’s incentive to replay from the beginning of the game in order to try and simply attain a better score.

It’s actually rather addictive to go “from the top” and see how efficiently you can reach later stages of the game without taking damage or losing lives — plus if you do ever make it to Havok himself, you’ll get a hefty bonus according to how many lives you have left, so there’s incentive to try and get through as unscathed as possible!

Switchblade’s relatively sedate pacing and clunky controls might put off gamers used to platformers with a bit more fluidity about them, but it remains an interesting early example of the open-structure 2D platformer, as well as an intriguing look at a Brit’s-eye view of what a “Japanese-style” video game really is.

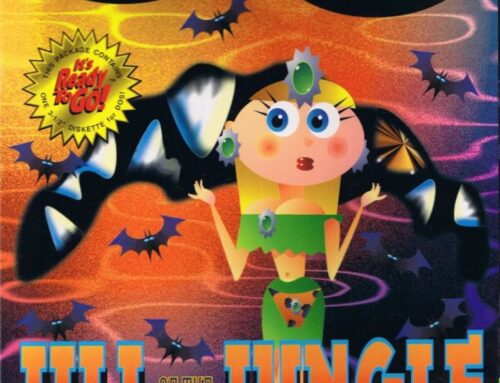

The packaged Jaguar version comes with a lovely full colour manual and box featuring art by Phipps himself, too, so you can display the game on your shelf with pride. Because let’s face it — if you own an Atari Jaguar, you’re almost certainly someone who likes showing off the lesser-known or more underappreciated titles in your collection, aren’t you?

Switchblade was available from our friends at Funstock, but is now unfortunately sold out. You can still pick up a copy direct from Piko Interactive, though!